Sponsored by the Royal Canadian Geographical Society, the Arctic on the Edge/L’Arctique à la limite Expedition documents the life cycle of ice from Greenland to Baffin Island, south down the Labrador Coast, ending in Newfoundland.

The polar region is warming more than twice as fast as the rest of the planet. That means that our northern geography is changing faster than anywhere else on earth. The scientific journal Nature reported in April 2017 that the Arctic is 3°C warmer now than baseline data from 1971 to 2000. The evidence is clear. The Arctic is undergoing a massive transformation at a time when we have barely documented what lies at the interface between the sea rapidly depleting ice. Arctic on the Edge will take a close look at the journey of sea ice and how it is transforming humanity and the natural world.

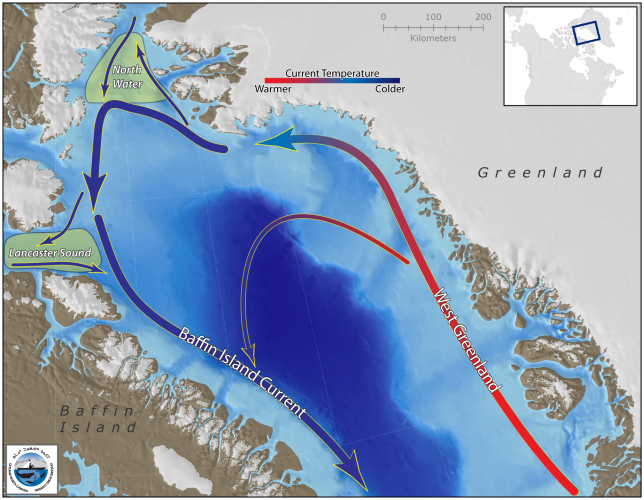

The story of sea ice begins in Greenland where glacial deposits meet calving grounds along the coast. In sheltered inlets, bays and fjords, glaciers march towards the ocean and break off into the sea. From there, they begin a voyage across the Davis Strait to Baffin Island and then, after a winter of sojourn, they continue south along the Labrador Coast to Newfoundland. In early 2017, reports indicate that ice conditions between Newfoundland and southern Labrador were the worst in recorded history hampering shipping and fishermen from their normal routes.

The Canadian Ice Service reported above normal ice melt in 2016, generally occurring 1-2 weeks ahead of normal across most of the Canadian Arctic, with some regions remaining 2-3 weeks ahead through the summer. By early September, ice cover was the third-lowest on record, behind 2012 and 2011. With changing ice conditions comes a change in the way of life for people and wildlife in the Arctic.

In March 2017, Jill Heinerth was presented with the Polar Medal by the Governor General of Canada at a ceremony in London, Ontario. The Polar Medal celebrates Canada’s northern heritage and recognizes persons who render extraordinary services in the polar regions and in Canada’s North. As an official honour created by the Crown, the Polar Medal is part of the Canadian Honours System.

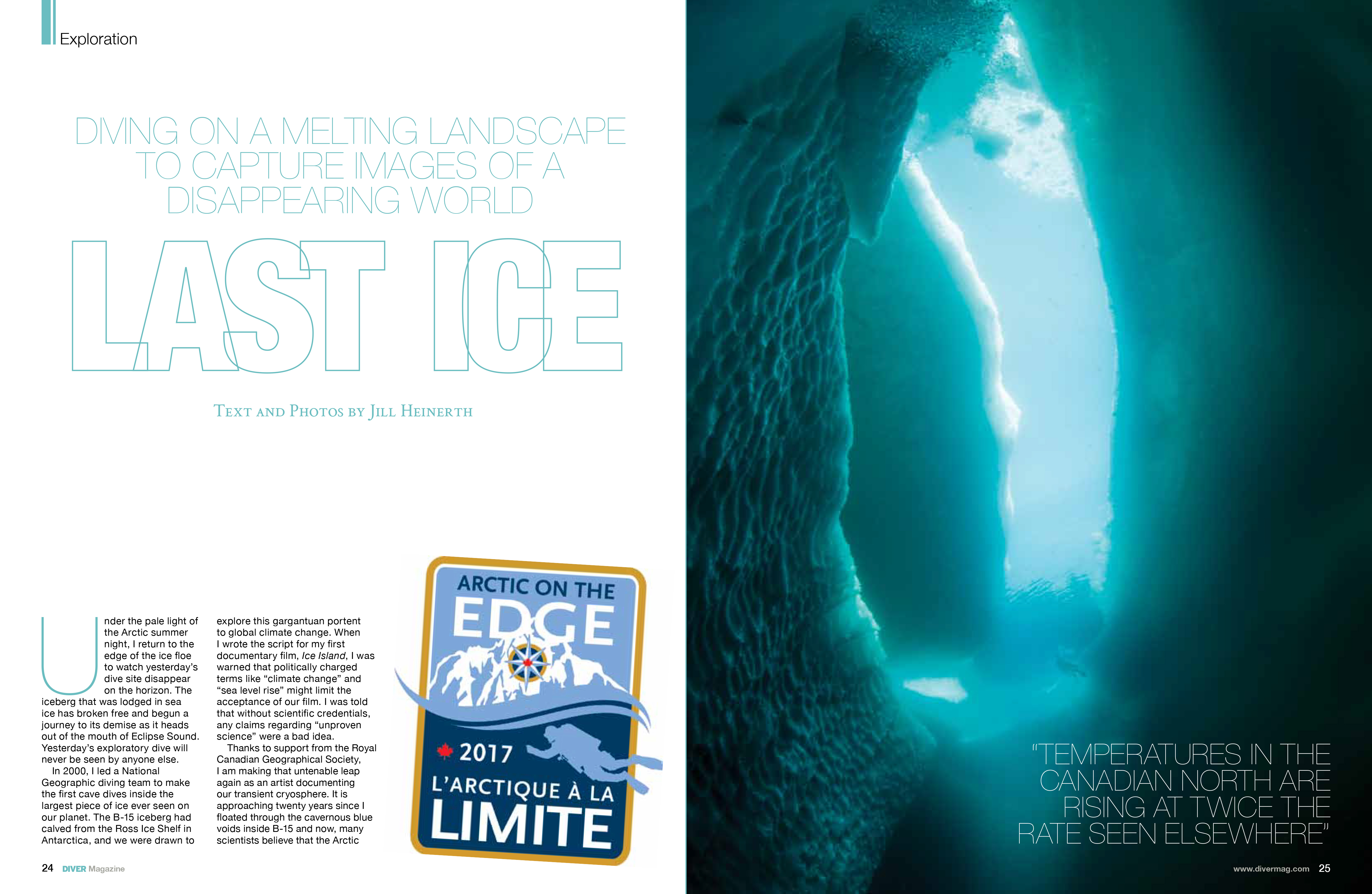

READ: Last Ice in DIVER Magazine Diving the transitional environments of Bylot Island by Jill Heinerth

Freshwater from the river source at the base of Nachvak Fjord, floats above the colder dense sea water and freezes in a thin layer of “grease” ice that sounds like thin broken glass being swept up into a dustpan, as the hull of Ocean Endeavour carves its path. Glaciers sculpted these fjords, composed of Precambrian Gneisses that are among the oldest rocks on earth (3.9 billion years old), into eastern Canada’s highest elevations of 1,652 metres ( 5,420 ft). There are currently over 100 small mountain glaciers still carving out new terrain in this mountain park. Torngat Mountain National Park…

I’m not a scientist. The funny thing is that sometimes I play someone that sounds like a scientist on TV. My professional training is as an artist. My written articles will never be published in a scientific journal, but I hope my photography, films and art will connect people with the world they might not get to see on their own.

South Shore Bylot Island In 1931, Group of Seven artist Lawren Harris painted a series of canvases of an Arctic landscape that captivated my imagination since my childhood. I will now have the privilege of visiting the very spot on the South shore of Bylot Island where he coaxed his oils into masterpieces that have netted as much as $2.43 million dollars. The Group of Seven is undoubtedly one of the most influential art movements in Canadian history. They captured the Canadian landscape in a way that nobody had done before. Franklin Carmichael (1890–1945), Lawren Harris (1885–1970), A. Y. Jackson (1882–1974),…

Please considering supporting:

Climate Regulation

Ocean currents transport warm water and precipitation from the equator to the poles and cold water from the poles back to the tropics on a global conveyor system that regulates the world’s climate.

Deep Ocean Circulation

Deep-ocean currents and atmospheric circulation work together to transport massive amounts of heat and salt around the globe. Sunlight warmed water at the equator flows into the North Atlantic, where it is cooled and becomes saltier through evaporation. Cold, salty water is heavy and drops to the seafloor forming a massive undersea river. The deep water flows through the world’s oceans on a current-driven conveyor, rising in places where winds sweep away warm surface water. Freshwater evaporated from the Atlantic falls as rain on the Pacific, diluting the upwelling salty water with freshwater and restoring balance.

Surface Ocean Currents

The wind drives surface currents and in turn, influences atmospheric circulation. Both ocean and atmospheric circulation are shaped by the spin of the Earth. Surface currents form massive circular patterns called gyres that, because of the Earth’s rotation, flow clockwise in the northern hemisphere and counterclockwise in the Southern Hemisphere. Currents, on the edges of the gyres, carry warm tropical water to higher latitudes and cold polar water to the lower latitudes.

Loss of Sea Ice

NASA’s cryospheric scientist Dr. Walt Meier narrates this important visual. documenting changes in Arctic sea ice between 1984 and 2016. An updated version of this visualization can be downloaded in HD here.

The Problem

Global ice cover has been deteriorating for a long time. Over 50,000 years ago, the world’s ice sheets were so large that they held enough water to lower the world’s water level almost 400 feet. But around 25,000 thousand years ago, the ice sheets started melting, and shorelines slowly receded inland by as much as one hundred miles. Some of those remarkable ice sheets are still melting today at an ever accelerating rate, and the fate of ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica will dictate the future geography of our planet.

The population of the planet is nearing 8 billion with hundreds of millions of people living on coastlines that provide real estate and resources, all within a few feet of current sea levels.