Dry gloves can be frustrating, expensive, and difficult to manage without assistance. In this video, I explain a simple method the keeps me cozy.

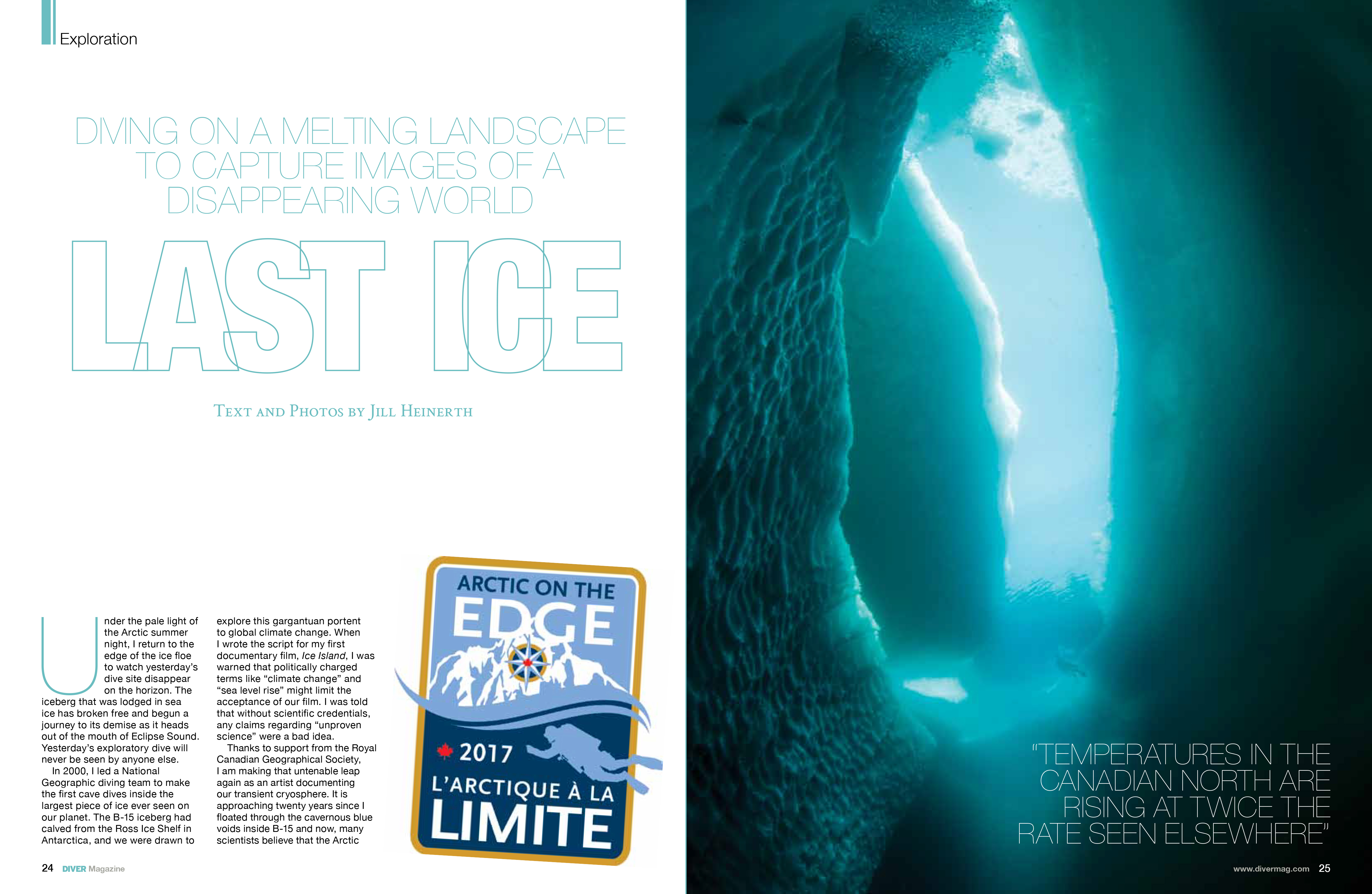

Sponsored by the Royal Canadian Geographical Society, the Arctic on the Edge/L’Arctique à la limite Expedition documents the life cycle of ice from Greenland to Baffin Island, south down the Labrador Coast, ending in Newfoundland.

The polar region is warming more than twice as fast as the rest of the planet. That means that our northern geography is changing faster than anywhere else on earth. The scientific journal Nature reported in April 2017 that the Arctic is 3°C warmer now than baseline data from 1971 to 2000. The evidence is clear. The Arctic is undergoing a massive transformation at a time when we have barely documented what lies at the interface between the sea rapidly depleting ice. Arctic on the Edge will take a close look at the journey of sea ice and how it is transforming humanity and the natural world.

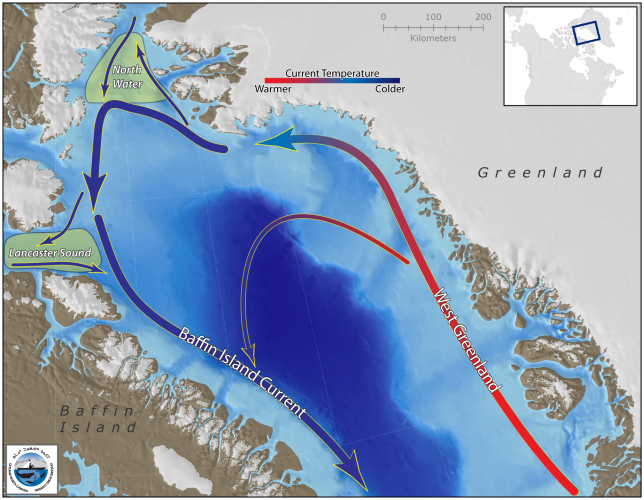

The story of sea ice begins in Greenland where glacial deposits meet calving grounds along the coast. In sheltered inlets, bays and fjords, glaciers march towards the ocean and break off into the sea. From there, they begin a voyage across the Davis Strait to Baffin Island and then, after a winter of sojourn, they continue south along the Labrador Coast to Newfoundland. In early 2017, reports indicate that ice conditions between Newfoundland and southern Labrador were the worst in recorded history hampering shipping and fishermen from their normal routes.

The Canadian Ice Service reported above normal ice melt in 2016, generally occurring 1-2 weeks ahead of normal across most of the Canadian Arctic, with some regions remaining 2-3 weeks ahead through the summer. By early September, ice cover was the third-lowest on record, behind 2012 and 2011. With changing ice conditions comes a change in the way of life for people and wildlife in the Arctic.

In March 2017, Jill Heinerth was presented with the Polar Medal by the Governor General of Canada at a ceremony in London, Ontario. The Polar Medal celebrates Canada’s northern heritage and recognizes persons who render extraordinary services in the polar regions and in Canada’s North. As an official honour created by the Crown, the Polar Medal is part of the Canadian Honours System.

READ: Last Ice in DIVER Magazine Diving the transitional environments of Bylot Island by Jill Heinerth

Under Thin Ice In the fall of 2018, I was shooting a film called Under Thin Ice for the Nature of Things on CBC. My colleague and fellow filmmaker Mario Cyr, suggested that we work together to get a shot of a polar bear swimming in the open water. As the icons of climate change, these amazing animals normally hunt on top of the ice, but climate change has forced them into the water to find food – a sevenfold increase of time in the water over the ice. Polar bears can swim 10 kph for 10 days without stopping…

Dive into the remarkable underwater vistas of Canada through this series on Scuba Diving Magazine. From the Arctic to the Pacific, Atlantic, and Great Lakes/St. Lawrence Seaway, Canada has the longest coastline in the world. Eight percent of the landscape is covered by lakes, greater than any other country. I’ll never be able to experience more than a drop in the bucket of diving opportunities, but last year, I completed my goal to take a plunge in every province and territory. This five-part web series offers a peek into what gets Canadian divers excited about their home waters. PART ONE…

Reliable drysuits are critical for survival and comfort in cold water. Without proper exposure protection, one could expect to survive for less than 45 minutes in water that is near freezing. In less than 15 minutes, unconsciousness would be likely. The best drysuits are custom-tailored and manufactured with custom features. When wearing heavy layers, you still need good range of motion. A drysuit should be light and soft but also durable and flexible. A cold-water hood should be made with supple, stretchy neoprene that seals well on the face. Undergarments must be of a technical variety that will retain insulation…

Scuba regulators are life-support devices. When you use these under ice and in extreme temperatures, it is important to have confidence in their operation. Regulator free-flows are one of the most significant hazards when diving under ice or in very cold water (less than 4°C). The sudden drop in pressure causes the condition as air passes from the cylinder through the first stage. When high-pressure air passes through the first-stage, it hyper-cools the metal moving parts. In a piston reg, small ice crystals can block the piston open, causing more airflow and trapping the piston open, creating a vicious feedback…

Shooting the dancing colors of the northern lights is often a part of a trip of a lifetime. It is critical to have the right gear and settings to capture the stunning visuals to share with your friends. Bring a high-quality tripod capable of stabilization for a 10-20 second exposure. Carbon fiber is lighter and easier to handle than metal. Your camera should be capable of working in Manual Mode so that you can control aperture, ISO, and shutter speed. Check the aurora forecast for your area to determine if and when they might peak. The aurora activity is described…

Shooting in the polar regions offers some incredible opportunities for capturing rare wildlife sightings and natural phenomena such as the northern lights. To make the best of your trip, be prepared for the cold. The following tips will help you protect your camera, batteries, and body from the chill. Store extra batteries fully charged and warm inside your parka. I use the inside chest pocket, so they are close to my body. Bring at least three camera batteries so that you have two spares ready to go. You don’t want to miss a shot when the low temperatures shorten the…

Please considering supporting:

Climate Regulation

Ocean currents transport warm water and precipitation from the equator to the poles and cold water from the poles back to the tropics on a global conveyor system that regulates the world’s climate.

Deep Ocean Circulation

Deep-ocean currents and atmospheric circulation work together to transport massive amounts of heat and salt around the globe. Sunlight warmed water at the equator flows into the North Atlantic, where it is cooled and becomes saltier through evaporation. Cold, salty water is heavy and drops to the seafloor forming a massive undersea river. The deep water flows through the world’s oceans on a current-driven conveyor, rising in places where winds sweep away warm surface water. Freshwater evaporated from the Atlantic falls as rain on the Pacific, diluting the upwelling salty water with freshwater and restoring balance.

Surface Ocean Currents

The wind drives surface currents and in turn, influences atmospheric circulation. Both ocean and atmospheric circulation are shaped by the spin of the Earth. Surface currents form massive circular patterns called gyres that, because of the Earth’s rotation, flow clockwise in the northern hemisphere and counterclockwise in the Southern Hemisphere. Currents, on the edges of the gyres, carry warm tropical water to higher latitudes and cold polar water to the lower latitudes.

Loss of Sea Ice

NASA’s cryospheric scientist Dr. Walt Meier narrates this important visual. documenting changes in Arctic sea ice between 1984 and 2016. An updated version of this visualization can be downloaded in HD here.

The Problem

Global ice cover has been deteriorating for a long time. Over 50,000 years ago, the world’s ice sheets were so large that they held enough water to lower the world’s water level almost 400 feet. But around 25,000 thousand years ago, the ice sheets started melting, and shorelines slowly receded inland by as much as one hundred miles. Some of those remarkable ice sheets are still melting today at an ever accelerating rate, and the fate of ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica will dictate the future geography of our planet.

The population of the planet is nearing 8 billion with hundreds of millions of people living on coastlines that provide real estate and resources, all within a few feet of current sea levels.